I was talking to a CEO the other day who wanted his people, particularly his senior managers to 'stand on their own two feet' as he put it. In short he wanted his people to become more entrepreneurial, creative, innovative and to be better critical thinkers. This is probably one of the more common requests I get in terms of senior management development and is a core activity of mine as it has at it's heart the ability to deal with ambiguity.

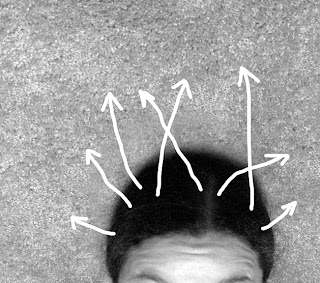

Successful acts of innovation, creativity and entrepreneurialism in particular are defined by the individual's ability to hold, cope and be persistent in situations that are highly ambiguous. Few true entrepreneurs create businesses using a step-by-step 'it's all mapped out' approach. Rather they feel their way forwards, frequently changing direction, often changing their business to meet prevailing conditions and succeed.

For example an indian restaurant set up in an out-of-town cinema complex just outside Oxford about five years ago. It was designed as a high end, sophisticated and elegant eatery. The business struggled for years. The problem is the restaurant is in a concrete cinema complex right next door to a very popular 'eat-as-much-as-you-want' fixed price chinese buffet. The chinese buffet would have queues outside whilst the indian was empty. A quick look in the vast car park outside was all the data you needed about the socio-economic profile of the typical customer to the complex, these are certainly not high end vehicles. As they say, necessity is the mother of invention. After struggling for years the business changed tack and is now an eat-as-much-as-you-want fixed price indian buffet. It is now a popular business with a reasonable turnover. They changed their business strategy, (eventually) and appeared to have saved they day.

The problem, in many organisations and companies is that most managers grow up and are promoted for compliance and regulating people, not for being maverick agents of innovation and change. Most organisations require layers of agreement (and meetings) for any change to occur. Being a creative and innovative entrepreneur, in many organisations is a bit like trying to melt an iceberg with the aid of a soggy box of matches.

So, can you change someone from being an agent of compliance into an entrepreneurial being. The short answer is yes, in many (not all) cases. However if the organisational systems promote compliance and regulation this is very hard to achieve and will certainly create 'drag' in the entrepreneurial aspirations of the company.

Successful acts of innovation, creativity and entrepreneurialism in particular are defined by the individual's ability to hold, cope and be persistent in situations that are highly ambiguous. Few true entrepreneurs create businesses using a step-by-step 'it's all mapped out' approach. Rather they feel their way forwards, frequently changing direction, often changing their business to meet prevailing conditions and succeed.

For example an indian restaurant set up in an out-of-town cinema complex just outside Oxford about five years ago. It was designed as a high end, sophisticated and elegant eatery. The business struggled for years. The problem is the restaurant is in a concrete cinema complex right next door to a very popular 'eat-as-much-as-you-want' fixed price chinese buffet. The chinese buffet would have queues outside whilst the indian was empty. A quick look in the vast car park outside was all the data you needed about the socio-economic profile of the typical customer to the complex, these are certainly not high end vehicles. As they say, necessity is the mother of invention. After struggling for years the business changed tack and is now an eat-as-much-as-you-want fixed price indian buffet. It is now a popular business with a reasonable turnover. They changed their business strategy, (eventually) and appeared to have saved they day.

The problem, in many organisations and companies is that most managers grow up and are promoted for compliance and regulating people, not for being maverick agents of innovation and change. Most organisations require layers of agreement (and meetings) for any change to occur. Being a creative and innovative entrepreneur, in many organisations is a bit like trying to melt an iceberg with the aid of a soggy box of matches.

So, can you change someone from being an agent of compliance into an entrepreneurial being. The short answer is yes, in many (not all) cases. However if the organisational systems promote compliance and regulation this is very hard to achieve and will certainly create 'drag' in the entrepreneurial aspirations of the company.