What we didn't let the Romans do for us.

Vindolanda was build c AD 300, 1712 years ago and was one of a series of such forts. Each fort was connected to a network of proper all weather roads complete with drainage and a complete set of traffic regulations.

'So what happened when the Romans left 'my son asked?

I had to think.

What happened when the Romans did pull out was that we the indigenous Britons not only ignored the technology left behind but dismantled their buildings and roads to build huts! It took us over a thousand years to get back to similar levels of sanitation and general living standards.

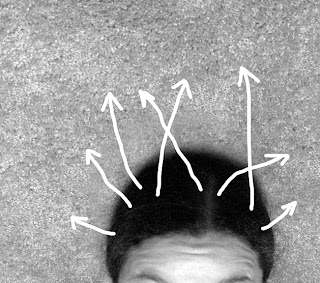

This is a wonderful example of a hermetic or non-permeable learning system whereby learning available outside of the current system and set of constructs is ignored and not even recognised as something to learn from. This isn't so much a case of reinventing the wheel, it's more like throwing the wheels away because we are too busy developing new ways of dragging things around.

I travel a lot and last month I drove through Africa. 11,000 km from Durban to Capetown, up through Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Malawi, Mozambique, Swaziland and back into South Africa. Each country was as different as it was possible to be. You crossed the border and it was like stepping into another world. The distance of less than one hundred yards could make all the difference between home made brick built houses with windows, fire places and sanitation or poorly constructed mud huts. People sitting at the side of the road begging, to productive small businesses sprouting up everywhere. Desolate bush to productive and well managed farms. Squalor to well decorated and organised villages all within a few hundred yards of each other and this isn't down to national poverty rates. The transition from Zambia to Malawi for example couldn't have been more stark. In terms of GDP Zambia ranks as the 139th highest in the world according to the latest figures from the IMF. Malawi is 4th from the bottom of the list at 180th and yet you would not know it looking at the difference between the countries. Zambia is largely run down, pothole strewn and has all the hallmarks of a failed state. Malawi is neat, clean and everyone is an entrepreneur, with smart roadside shops and amazingly organised villages.

I also travel a lot from organisation to organisation and government to government. Each one is different, and like the early Britons and the populations of the countries I visit, I see and experience the same hermetic learning systems where people fail to walk next door and learn. I marvel when I get appalling service in a restaurant, or end up in a poorly managed hotel for example. Do these people not visit other restraunts and hotels? Do they not see what would transform their business? No, would appear to be the answer. it would appear the Romans did sod all for us. Not because of them, but because we didn't get it. The system was too advanced for us to make the leap and think, 'clean water direct to the house and sewerage systems' are neat ideas lets copy. Nope our response was to dismantle the technology so we could chuck the stones at each other, go to a well for our water and poo in the river. We only learn things that are in our system or close enough to it for us to grasp, even if it is given or left to us on a plate.

Now about the current economic and political situation....